The fount was lost amidst the rocks

The saint was lost among the thieves;

In the homes of the ignorant the wise pandit was lost;

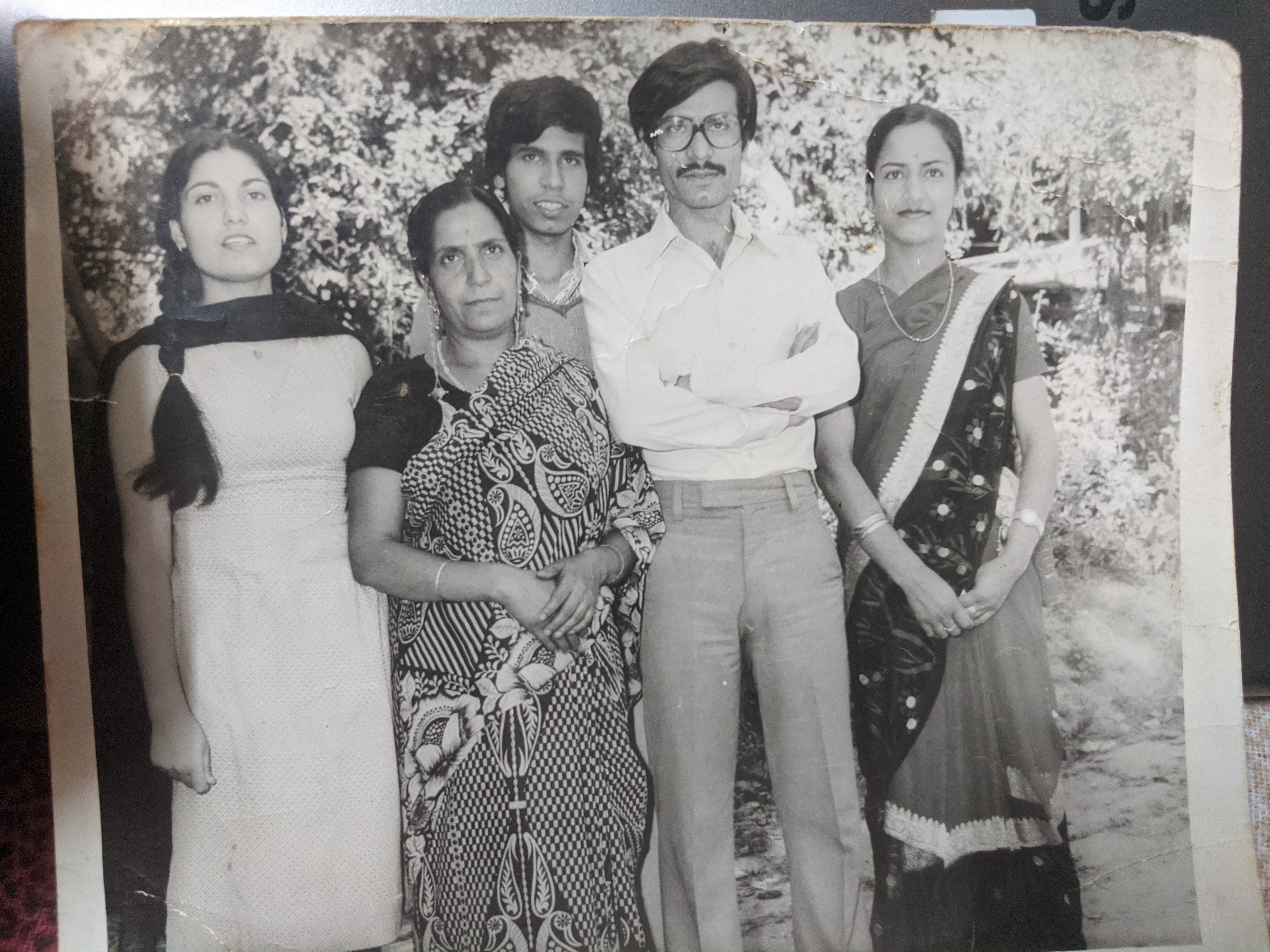

My mother doesn’t expect me to remember this special place she used to take me. ‘You were too young,’ She always says. Back then my mother was a young government teacher, serving in a school at a place simply called Tsrar by Kashmiris. These were the first few and the only ‘working’ years of her life. She was learning to cook. She was newly married. She would travel to work from Chattabal to Tsrar, take a tempo to Iqbal Park, then a short walk to New Tsrar Adda, and then a bus to Tsar. In the bus she would often fall asleep on her seat. One time, after she accidentally head bumped a fellow passenger, she took to knitting in bus, just to stay awake. You can’t read books on bumpy bus rides. Knitting sweaters on the other hand is an enticing option. Soon her hands, in true old school teaching tradition, were always knitting. She kept at it even as he sat upon a class. One time she even came close to getting busted by the headmistress. That time, on being jumped by the headmistress, my mother hid the sweater she was knitting for me under her arms, holding on tightly to it under her shawl, even as the suspicious headmistress asked her to hand over the roll-register, the question papers, the chalk, the duster and finally that piece of paper in the corner of the classroom. My mother just held on to that sweater under her left arm. When the headmistress left, my mother looked out the window and sent a little prayer of thanks in the direction of the wooden minaret that stood over the ancient saint’s last resting place. While she served in that town, she would visit the shrine ritually, almost everyday. On some days, when I had no school, maybe a Christian holiday or a non-gazetted holiday or maybe on a second Saturday, she would take me along.

‘You don’t remember do you? If only could go there again! It was a good place.’

vethavavas tan nani su ti doha Nasaro

ton vagara ta syan pani su ti doha Nasaro

The body exposed to the cold river winds blowing,

Thin porridge and half-boiled vegetables to eat-

There was a day, O Nasaro

My spouse by my side and a warm blanket to cover us,

A sumptuous meal and fish to eat-

There was a day, O Nasaro

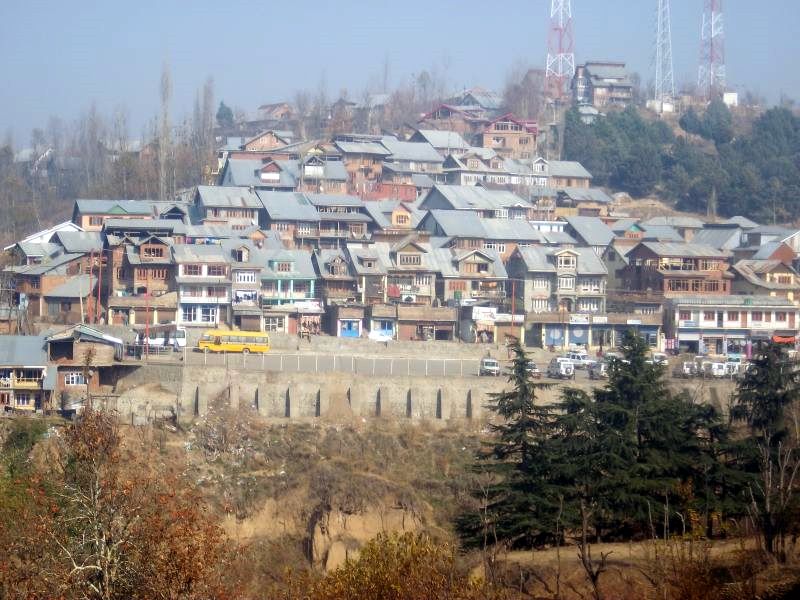

I don’t remember. But then… the only memory this place brings to my mind is that of a lunch break spent in my mother’s school staff room dreading the thought of having to eat Girdas that looked menacingly fungal red, felt soggy and but were in fact just mildly painted in red of sweet mix-fruit Kisaan Jam. For the window of the staff room, the town looked grey, the color of galvanized tin and then there was the minaret. I didn’t like the thought of being there. Maybe one of the reasons why in coming years minarets were going to make my nightmares interesting – rows and rows of houses with minarets slow growing from them. Or maybe the fact that I was spending a holiday in a school wasn’t much appreciated by me.

‘I won’t eat that.’

‘You don’t have to,’ a colleague of my mother came to my rescue. ‘You should take more care about what he eats. This is the time to eat. He should be eating.’ And that day I didn’t have to eat those sad Girdas.

After a couple of years working in Tsrar, service was to take her to a village more nearer to our house, it was to take her to a village called Durbal. She would take me to this place too. To the house with a solitary walnut tree. House just beyond a brook that roared like a perpetually angry lion. At Durbal, I came to form an opinion that good walnuts are delightfully sticky when green and fresh, but maybe not eatable. Here, while knitting in class room, my mother came to form an opinion or two about her students and their families and religion. Poor. Simple. Honest. God fearing. Not very bright. Funny. Tough. Once she gave a tough time to a girl student in her class. Went corporal on her, which of course was and may be still the norm in that part of the world. Next day poor girl’s parents reached the school along with half the village. Mother thought she was going to get lynched. Instead, the parents of the girl thanked her profusely and asked her to be even more strict next time. ‘ghaanch kariv sa, take her limbs apart. Make her read.’

Traveling to a remote village for work was a fearful proposition for my mother. Muslims. We were nearing 1990. Things were changing. One time there was some trouble in the city, people were out on streets, roads from village to the city were blocked, and my mother found herself on road, trapped somewhere in some village. That day, fearful for her life, she took shelter in the house of a farmer. ‘There were sharp edged instruments in that house. Sickles and what not. That must have been a Shia family. Shias are okay, I guess.’ He reached home safe and sound that day too.

A classic ‘Kashmir’ narrative. Of students gone rebel. In her class was a kid named Bobby Khan, a last bencher, a brick head, a troublesome menace for a teacher, any teacher. All good classes have such characters. They add character to a class.Years later, one of my mother’s interesting conversations about her school time would always have a line about ‘Bobby Khan who became militant. Died. Not very bright.’ Some years back, I actually managed to meet one of her students, a namesake of Bobby Khan. This Bobby went to the same school as my mother’s nephews, a private school where she taught for some time, a revolutionary new school named after a poem by Thoreau, the kind of school that didn’t think twice about taking its students to see a film like Satyam Shivam Sundaram. Bobby now worked is Saudi Arabia and had come to meet his old friends living in Noida. After the formal introduction – ‘he’s your teacher’s son’ – we had an interesting discussion on music of Cheb Khaled and the beauty of original ‘Aïcha’.

That almost sums up her entire teaching experience, a period of more than twenty years. Of these twenty years, only six or five years were spent at the job because a few years later, we were in Jammu. She was not to teach in a school ever again, nor ever to fall asleep on way to work, nor do any fancy knitting at work. Knitting at home must not be engaging, I don’t remember her knitting even though her knitting kit did reach Jammu with her. Later, as retirement closed in on her, she was to come to the conclusion that it would have been better if she had instead brought a properly fixed attested service-book along with her to Jammu. There were glaring gaps in her service-book. And without proper service-book there is no proper retirement. Retirement time can be one of the busiest time for a government servant. Fixing records. Running around. Getting clearance. One can’t afford to mess with this process or miss a single step. During this phase of her career, she took to recounting an interesting case of ‘retirement-clearance’. A woman’s clearance was put on hold because it was revealed during the cross-checking of documents that the said woman’s birthday fell on 31st February every year. The woman’s retirement plans took a costly hit. Retirement is serious business. So a couple of years before her retirement, with worries like these, my mother thought of clearing her records. At first her brother helped as he was posted in Kashmir at the time. Later her husband, my father went about the job of visiting various offices and head-offices in Kashmir to set her record straight as he was posted to Kashmir. A stamp here, a sign there, something for the kids there, a simple gift for Sahibs big and small. Things were moving. During these trips one of the biggest hurdle proved to be getting an okay for the time-period, a particular period spanning 6-8 months of her career. It turned put that during this period some unknown or known person in Kashmir was drawing salary in my mother’s name while she too was drawing a salary in Jammu. In time, even this problem proved to be a no-problem and was resolved. Both parties were kept happy. Files and paperwork were sorted out accordingly as nothing could be found on digging deeper into the case. Finally a year away from her retirement, the only part of her service-record that needed entries and signatures was for the time that she spent working in Tsrar.

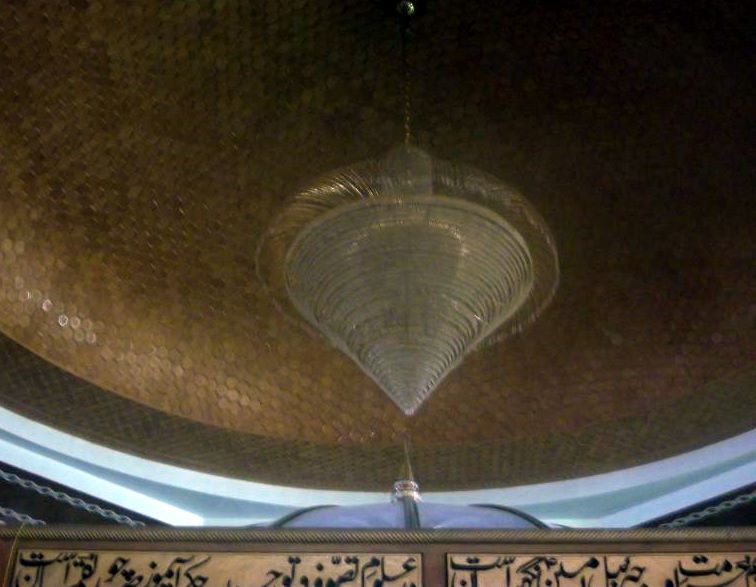

At the start of that year, my father was ordered to report back to work in Srinagar, this was after a gap of about twenty years. Government was pushing for something. He was allocated a department and a division. He got himself a room in a hotel, was shacked up with a bunch of other pandits. It wasn’t going to last. At the end of the year, his division was again going to change and he was going to be out of Kashmir again. But before he moved out of Kashmir, certain service records needed to be fixed, his own and his wife’s. For his wife’s service record he was to visit Tsrar. While in Tsrar a visit to the shrine was mandatory.

On a computer screen, as I looked at the photographs of the place that still looked as if painted in the color of galvanized tin, my mother told me about the call that my father made to her from an office in Tsrar. In the government office at Tsrar, the file bearing my mother’s name had found its way to the table of a woman who claimed to recognize my mother’s name and claimed to have been taught by my mother. My father thinking of it as a good sign. Thinking, maybe the file will closed, finally, rang up my mother, explained the situation to her and handed over his mobile to the woman officer. The two woman talked.

‘We talked. But I have no idea who that girl was. Couldn’t recall anything!’

Mother too had forgotten something. I stared at the pixels that shaped the new stoney minaret that stands over the ancient saint’s last resting place. I remembered things.

Love is death of an only son to a mother –

Can the lover have any sleep?

Can the lover have any rest?

Love is a robe dripping with blood-

-0-

|

| 20 miles south west of Srinagar, perched on a dry bare Hill, the tomb of Nund Rishi at a place called Charar Sharif. |

|

| 2010 |

-0-

Lines of Nund Ryosh from ‘Kashmiri Lyrics’ by J.L. Kaul.

Dear,

Knitting in school was a common practice followed by almost all the government teachers. My mother was a government teacher, and I remember her knitting like anything at any place. Now thanks to technology which yields us with good varieties of woolen sweaters, due to which this custom of knitting among teachers had been completely abolished. Today’s peace was wonderful and it makes me remember the old childhood days.

Thanks

Faheem

Thanks for the comment!

Yus gachyi Bumzoo, Chrar, Muqam

Tas chhuy dozakhuk naar haraam

Jantas manz chhuy su garyi gare

Will post something about him soon.

I am very much interested in your website. it gives an insight of real Kashmiri culture. I have been living in Delhi for the last 6 years, but visiting your website makes me as I am just in the paradise, that is, Kashmir. Tsrar Sharief represents the real symbol of Hindu Muslim unity in Kashmir. I am really thankful to you for representing everything about Kashmir through this website.

Thanks

Syed Amir Ahmad