| Strange Tales from Tulamula Fish.

|

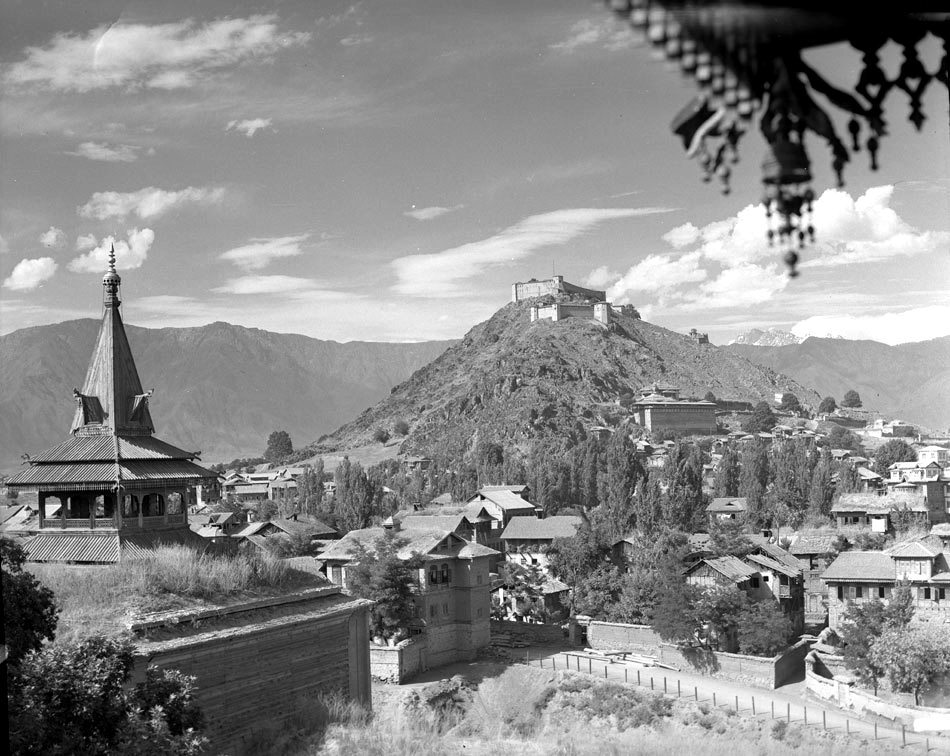

| Syen’dh at village Tulamulla. River originates in Gangbal-Harmukh and is not to be confused with Sindhu or Indus River. |

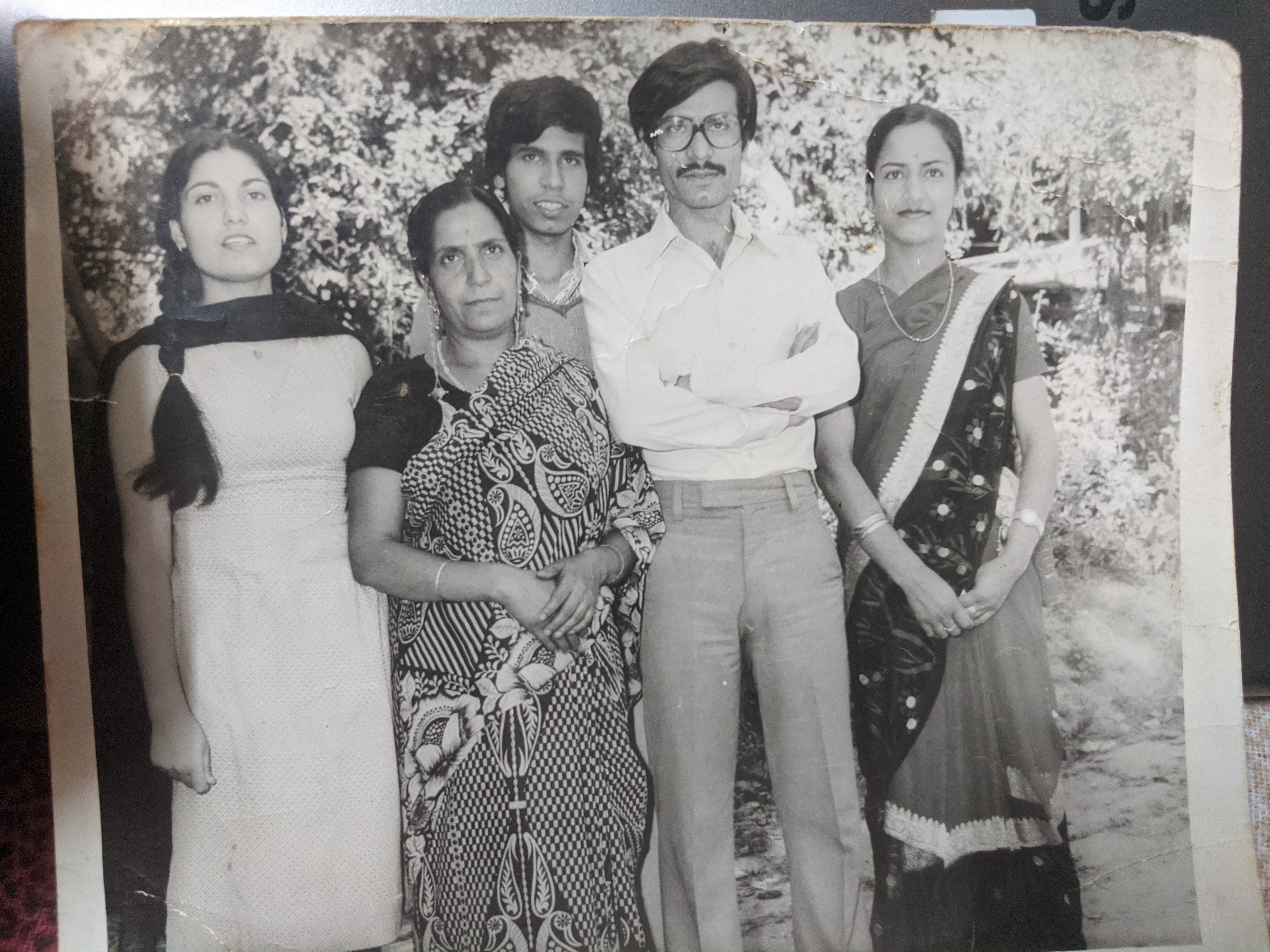

The feeling was that of disorientation. As I entered the Island, I was lost in some old memory of the place. A fleeting vision. And then I was lost, really lost. I somehow got separated from rest of the pilgrims that included my parents and relatives. None of them were in sight anymore even though we were all walking together moments ago. In front of me was an iron grilled door, but I didn’t know if it was the entrance or the exit. Towards right, I saw a security building and for some strange reason assumed that everyone must have gone inside it to get registered or something. I felt like staying lost for sometime more. I sat down at my old spot, little stone steps next to the footbridge over the stream that surrounds the island. And I scratched that old memory out:

I walked between innumerable pair of legs to get out of the frenzied melee around the spring. That sight: a man standing on a wooden plank over the milky whiteness of the spring, a bridge to the island, a bridge between deity and devotee, it was unnerving. It was like watching someone rope walk only there was no rope, only a piece of wood. Did the Priest, the conduit on this precariously placed plank know how deep the white spring went? How many meters below the level of flowers? All the pushing and shoving was getting a bit too much. What if I fell into the spring. Holy or not, I had no plans of measuring the depth of the spring. And one can barely see anything in this rush. I walked between innumerable pair of legs to get out of the frenzied melee around the spring. I went back to the stream. The devotees were still taking dips in its cold, dark waters. Even the thought of its water scared me. Earlier in the day, I had escaped the compulsory ritual bath thanks to my little drowning incident in the swimming pool of Biscoe. I was still a bit traumatized, even though it had been more than a month now. I told everyone in clear terms that I was never going into water ever again in my life. Now I sat on muddy, half broken and slippery steps that lead into the dark stream. I chose the spot next to the footbridge that connects the island to the village. There were people diving into the stream from the footbridge and there were kids my age frolicking in water, swimming. In the swimming pool, other kids had been holding onto a side bar with their both their hands while paddling their both feet in a synchronised. They was practising swimming. I learned drowning. I missed that little detail about holding onto something and started paddling my feet without holding onto anything. After I was pulled out of water by a Ladhaki instructor, I found myself in middle of the pool and I was still paddling. I had gulped down a good amount of water. I believe I would have died had I stayed underwater a bit longer. Or, maybe not. The instructed carried me to the side before the judge of my performance, the class teacher. I pleaded with the teacher to have me pulled out of the pool. I told her that these waters were going to kill me, that I was going to die. She calmly pointed at her watch and said there were still twenty minutes for the period to be over, there was still time. I cried. I held on to those sidebars for rest of the twenty minutes. On the ride back home, standing in the school bus, I vomited green water. My underwear was wet, it stuck to my skin me like an insult. I had completely forgotten that our class was to going to have swimming lessons starting that day and that we were supposed to bring a towel and an extra underwear to school. What stupidity! On reaching home I told my grandmother, I was never going back to that monstrous school. I laughed to myself. Swimming is for fish.

I noticed little black fish swimming in the shallows where the waters met the stairs. They would swim to the stairs and then swim back. I threw little pebbles at them, just to wake them up, to watch them swim. I always liked fish. I named my grandmother’s sister, Machliwalli Massi, only because her house at Rainawari overlooked Jhelum. The first time my grandmother wanted me to go to her sister’s place, I wanted to know if I could see fish from some window of the house since it was on the river bank bank. She said indeed I will. I was disappointed, no fish from the window, even the river was a bit far from the house, it wasn’t on the river, but there was some beauty to it, and the name stuck. She remained my Machliwalli Massi even after her family moved to Jhallandar. Even as she lost her memories to old age.

|

| A devotee praying on one leg. Summer 2008. |

-0-